The United States should be talking with and pressing its allies to develop their own anti-access capabilities rather than replicating the power projection capabilities of US forces. Doing so would help ensure that the United States and its allies and partners have the capabilities needed to credibly deny Beijing the ability to invade or coerce Taiwan.

How would American allies in Asia react to a major contingency between the United States and China, such as a crisis in the Taiwan Strait?1 Although conflict over Taiwan is not the only crisis scenario in the Indo-Pacific that could implicate the United States and its allies, recent developments have heightened concern about Taiwan specifically.

Tensions over the Taiwan Strait have escalated. Increased numbers of Chinese military aircraft have flown through the southwest corner of the island’s air defense identification zone (commonly referred to as an ADIZ), and Chinese state media explicitly frames the increase in military activity around the Strait as an “obvious countermeasure” to joint US-Japan military exercises near Taiwan.2 In response, the American chargé d’affaires in Canberra, Australia, disclosed in 2021 that the United States and Australia had discussed contingency plans for a military crisis over Taiwan,3 and Japanese media reported that the United States and Japan have established plans for joint operations under similar circumstances.4 Meanwhile, the crisis precipitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised a host of questions about the options available for US and allied support to Taiwan under a similar conflict scenario in the Indo-Pacific.

Based on what we know today, would America’s allies and partners provide support in the event of a military crisis over Taiwan? More importantly, how would they do so, and under what constraints or limitations would they do it? These are crucial questions for the United States and its allies and partners across the Indo-Pacific.

Xi Jinping’s own statements have led some American analysts to speculate that a serious crisis is around the corner. While Xi has continued to use the language of “peaceful reunification,” he has also tied unification more closely to the task of national rejuvenation, and he has said (in both 2013 and 2019) that the Taiwan problem cannot be handed down from generation to generation—implying a finite timetable, even if the deadline has never been clearly specified.5 These circumstances have led American and allied defense planners to think about a range of scenarios that could emerge in the Taiwan Strait and how America’s alliances and security partnerships would apply in these different contingencies.

Amid signs of increasing allied coordination, a number of analysts have warned American strategists and defense planners that they should be conservative in their assumptions about allied support and involvement. Former intelligence analyst John Culver, for example, expects “a chilling set of answers if you approached authoritative people in our treaty allies . . . and [asked] them in the event that China attacks Taiwan, will you back our military alliance?”6

Answers from the region itself have not been consistent. For example, although former Australian Defence Minister Peter Dutton said that it was inconceivable Canberra would not back Washington to defend Taiwan in a conflict,7 former Australian officials, such as retired Prime Minister Paul Keating, have pushed back, arguing that Taiwan is not a “vital interest” for Australia.8 And at the subnational level, Japan’s Okinawa prefecture has made clear that it opposes some aspects of the Japanese government’s shift toward enhanced coordination with the United States on Taiwan.9 These examples suggest that robust domestic political debates are ongoing in several allied countries.

Detailed thinking on this question is important—and overdue. With no sign that tensions over Taiwan will abate anytime soon, divergent expectations about allied involvement could not only threaten Washington’s relationships with key allies but also undermine America’s ability to deter a contingency with China in the first place.

In a contingency over Taiwan, one can imagine at least four possible scenarios for conflict initiation, each of varying likelihood. In all four scenarios, Beijing would probably make active efforts in the press and diplomatic forums to blame Taipei for the crisis or conflict, undermining domestic support among US allies in the region. Yet each scenario would create different political dynamics and implications for US allies, especially as the crisis extended over time.

Scenario 1. China directly attacks Taiwan and US and allied forces and bases.

Scenario 2. China directly attacks Taiwan but not US or allied forces and bases.

Scenario 3. China directly attacks Taiwan and US forces but not those of US allies.

Scenario 4. China coerces or pressures Taiwan but avoids targeting US or allied forces and bases.

In the first and most escalatory scenario, Beijing could attempt to invade Taiwan outright while launching first strikes against US forces in the region, including strikes on US bases in allied countries and potentially strikes on allied facilities, even if US forces are not present. Given the current basing locations of American forces in the region, this scenario would be most likely to result in Japan and perhaps the Philippines being forced immediately into an undesired contingency, but Australia, some Pacific islands, and South Korea could also be implicated.

Depending on the circumstances leading to the initiation of conflict, US allies may have little warning, meaning they could suddenly become participants in a contingency for which they are neither politically nor operationally prepared. Military and political responses would have to be carried out at rapid tempo under high pressure, as would any attempt at coordination with the United States or other international players.

In the second scenario, Beijing could attempt to invade Taiwan but avoid attacking both US forces and bases in the region and those of all US allies. This scenario presents Beijing with distinct military risks, as it leaves assets available closer to Taiwan for a US and allied response and diminishes the “tyranny of distance” that American planners often reference as a disadvantage in attempting to surge US forces across the western Pacific.

However, it also comes with political benefits for Beijing: Chinese leaders may well bank on the United States’s and allied countries’ reluctance to get dragged into a costly and potentially casualty-intensive shooting war—and on domestic politics to slow or constrain their provision of active military support while leaders and publics weigh various options for intervention. Depending on the time frame in which Beijing judges it could carry out an invasion, the political benefits of this approach might outweigh the military disadvantages in the minds of the Chinese leadership.

In the third scenario, Beijing could consider striking US forces or bases in the region but avoid hitting US allies directly, in an effort to split Washington from its key regional allies. (This is actually a spectrum of options in itself, because Beijing could strike US forces at sea or outside allied territory, or it could strike only US bases on allied territory but not the facilities of US allies themselves.) In this category of scenarios, America’s allies would be deciding whether to intervene in a cross-Strait conflict that they have not yet been directly implicated in, rather than responding to a direct attack on their own forces and personnel. Whether US allies invoke US treaty commitments for their own defense, of course, could also shape the level and speed of Washington’s response.

Under this scenario, we expect that Chinese media and diplomats would probably portray their restraint as an attempt to limit horizontal escalation of the conflict and shift blame solely to the United States and/or Taiwan. The effect of this shift could be to slow or complicate allied responses to the emergence of a crisis and to inhibit allied coordination in the early period of an unfolding contingency.

The fourth scenario, and perhaps the most likely, could be even more difficult from a coalition-building perspective. Beijing might seek to coerce Taiwan without invading—opting instead for some combination of an embargo, the seizure of remote islands, cyberattacks, and limited strikes short of a full invasion. In this case, the United States would have to calibrate its own actions while attempting to coordinate a regional response.

In this scenario, allied willingness to get involved would likely depend largely on perceptions of risk. If allied countries see more-limited applications of force by Beijing as signaling reduced commitment to the conflict on China’s part and indicating a lower risk of casualties, that perception might make them more willing to participate. On the other hand, a more limited scenario might incline allies in the region to view their own contributions as less necessary; if there is disagreement among allies over the necessity of participation and basing permissions, then coordination could prove particularly challenging. The end result could leave the United States with a smaller regional coalition, fewer access points, and uncertain political footing in the Indo-Pacific during a conflict that might become protracted and economically damaging to all countries in the region.

In the scenarios involving a direct invasion, the allies most likely to contribute forces would be Japan and Australia. They would likely desire more-defensive roles, acting as the alliance’s shields rather than its spears.10 They might allow US basing access, but this would be a politically fraught decision, particularly if US and allied forces were not targeted in an initial strike.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, the United States has engaged in active discussions and contingency planning for a military crisis over Taiwan with counterparts in Australia and Japan,11 and some recent articles have called for preparations around a Taiwan Strait conflict to become “a major priority for the U.S.-Japan alliance . . . driv[ing] force posture, procurement, and bilateral operational planning and exercises.”12 Although these discussions date back decades, in many senses they are still in the early stages, and publics in both the United States and allied countries are not yet familiar with likely contingencies and escalation possibilities.13

While the ground has undoubtedly shifted toward greater consultation on these issues, the United States must not overestimate the extent or stability of evolutions in thinking across the capitals of its allies and partners. Discussions of these issues are likely to remain difficult in both Tokyo and Canberra. Jeffrey Hornung notes that

Japan expects that the United States will consult with it prior to conducting combat operations to obtain Japan’s consent if the United States is considering using its bases in Japan to engage in armed conflict with another country when Japan itself is not a party to that conflict.14

And while some experts see Japan’s policy shifts on Taiwan as dramatic and far-reaching,15 other analysts take a more conservative view of these developments16 or argue that growing alignment on Taiwan has not removed underlying disagreements about how to respond in terms of defense procurement and planning.17 Meanwhile, despite strong statements of support from current Australian defense officials, other observers have pushed back, including Natasha Kassam and Richard McGregor, who argue that “Australia has no interest, or indeed ability, to be a decisive player in the Taiwan dispute.”18

Other allies—namely the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand— would be even less likely to commit their forces to engage in an American-led coalition. Although these countries—and partners such as Singapore— might allow basing access under certain circumstances, this would likely come with severe limitations.

USINDOPACOM comprises a wide swath of maritime territory, from India to Hawaii. It covers more than half of the world’s population, 36 countries, and 14 time zones.

For example, Seoul might be reluctant to do anything that could widen the conflict or open a second contingency involving the Korean Peninsula. Moreover, it would want to reserve its own forces for a peninsula-specific contingency (either related to Taiwan itself or emerging from Pyongyang’s willingness to take advantage of an unfolding crisis elsewhere in the region).19 The United States and South Korea would first have to agree on whether it makes more sense for Seoul to pursue a substantial contribution to allied efforts vis-à-vis Taiwan or whether South Korea’s energy would be best focused on securing the peninsula, freeing US forces to focus elsewhere. Even if they agree on the latter option, discussions on basing access and facilities use will still be necessary.

Seoul’s peacetime willingness to engage in consultations with the United States regarding Taiwan has been inhibited by South Korean leaders’ fear of antagonizing Beijing and thereby undermining pursuit of unification on the Korean Peninsula.20 One Korean analysis notes that a request from Washington for Seoul to participate in a freedom of navigation operation or a military conflict with China would put South Korea in a “compromising position,” in which Seoul will have to “reach an agreement with Washington about strategic flexibility.”21 It remains to be seen whether this will change with Yoon Suk-yeol’s election, given that he has promised a tougher stance on China.

Historical precedents are at work as well. After South Korea’s Roh administration expressed concern that the George W. Bush administration’s desire for “strategic flexibility” in the use of US forces based on the Korean Peninsula could drag South Korea into a US-China conflict, then–Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice promised to respect Seoul’s position that it “shall not be involved in a regional conflict in Northeast Asia against the will of the Korean people.”22

For these and other reasons, Jung Pak concludes, “Beijing perceives Seoul as the weakest link in the U.S. alliance network, given its perception of South Korea’s deference and history of accommodating China’s rise relative to other regional players.”23 All of these factors combine to limit Seoul’s likely involvement in the case of a cross-Strait military crisis or conflict and make advance coordination and mutual understanding on these issues within the alliance more difficult.

The Philippines and Thailand might be similarly skeptical of basing access, particularly given recent tensions between US leaders and their counterparts in Manila and Bangkok. While outgoing Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s skepticism of US reliability is well-known,24 Duterte expresses in extreme fashion sentiments that appear among nontrivial segments of the Philippine public and policy elite. Newly elected president Bongbong Marcos has publicly downplayed the 2016 arbitration decision that ruled in Manila’s favor against Beijing and floated instead the idea of striking a deal with Beijing to resolve disputes in the South China Sea.25

The Philippines’s foreign policy has traditionally oscillated between seeking more accommodation with Beijing and relying more heavily on the US alliance. Given the structure of Philippine politics, which depends heavily on the foreign policy beliefs and preferences of whoever occupies the presidency, these personal views could have significant long-term alliance implications.26 Marcos’s early statements after winning the presidency suggest that he may focus on improving relations with China, so US basing access throughout the Philippine archipelago is far from guaranteed in a US-China crisis.

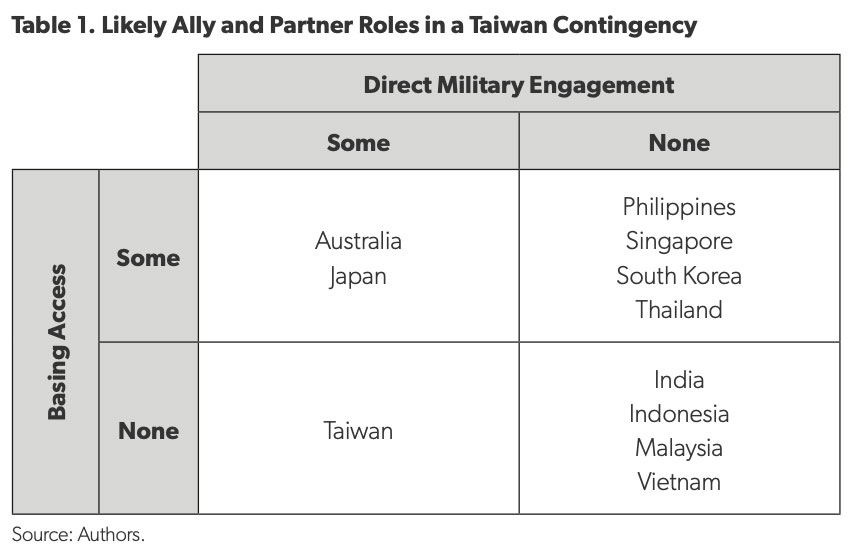

Finally, an even larger group of countries—including many concerned about China’s rise, such as Vietnam and India—would probably not contribute either forces or basing access. Many of these countries lack existing basing agreements with the United States, have limited experience operating jointly with US forces beyond basic training and exercises, and are likely to be worried about the economic fallout of actively opposing China in a crisis over something Beijing defines as a core interest. Joint operational concepts with these countries have not been tested, particularly the kinds of close coordination that would be needed in a major contingency. As shown in Table 1, the United States should not expect substantial force contributions or basing access from India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and most other regional players beyond those identified above.

Given the wide range of uncertainty on the specific timing and pathway into a possible future crisis, the United States must have a plan for a scenario in which political debates in any of these countries take center stage and potentially impede rapid and coordinated responses to a cross-Strait crisis. Therefore, in many (though not all) of these cases, the most realistic role the United States should expect from its allies and partners is the enhancing of their own defense capabilities, their security cooperation with the United States, and their security cooperation with each other, without a clear focus on a Taiwan contingency.

The United States should be clear-eyed about the fact that this kind of ally or partner role has ancillary benefits for broader American security interests, even when there is not explicit planning for involvement in a military crisis over Taiwan. Moreover, such activities do indirectly benefit preparations for a Taiwan contingency, as these developments around China’s periphery would “[ramp] up the challenges the PLA Navy, Marines, and Air Force would have to counter outside the Taiwan Strait” and reduce the Chinese military’s ability to prepare for a Taiwan contingency by “maximizing the range and complexity of challenges facing the PLA in other theaters.”27

As Joel Wuthnow has noted, this type of medium- to long-term activity puts pressure on a People’s Liberation Army organizational and command structure that is already designed for multiple smaller conflicts, not a single large one; distributes China’s resources away from its Eastern Theater Command; and raises the likely difficulty of internal crisis coordination on the Chinese side.28 In its regional diplomacy and messaging, therefore, the United States should make clear that it understands and values the contributions these partners make in the Indo-Pacific, even if they are not explicitly focused on Taiwan contingencies.

In short, despite the United States’s large number of regional allies and partners, if a major contingency erupts between China and the United States over Taiwan, Washington should expect to find itself working actively with only a small handful of willing contributors. Furthermore, it should expect that even those contributors may avoid the use of their forces or significantly restrain US access to their bases. It is important that the United States understands which allies and partners are capable of playing which roles, so it can appropriately calibrate its long-term activities in the region and its crisis planning.

The above dynamics could sharpen, not subside, if a conflict becomes protracted. As American analysts of the People’s Liberation Army have noted, a failed amphibious assault on Taiwan would not necessarily end the conflict. In an extended conflict, such as a blockade, Beijing would likely retain significant advantages over even the most robust US-led coalition,29 and little is known about how US allies and partners in the region would contribute to Taiwan’s ability to survive this kind of protracted scenario. For example, there has so far been almost no discussion about how America’s regional allies and partners might view, let alone participate in, activities such as resupplying Taiwan in the face of a Chinese blockade or engaging in mine-clearing operations.

Casualty sensitivity is another major unknown in considering protracted conflict. It is difficult at present to gauge the United States’s tolerance for casualties in a potential cross-Strait conflict,30 unclear how casualty sensitivity might influence Taiwan’s willingness to resist over a prolonged period, and hard to assess how strong Beijing’s will would be to engage in a protracted attempt to take the island, especially if the PLA suffers heavy casualties during the initial fighting. The general rule that autocracies tolerate higher casualties than democracies depends somewhat on conscription rates, whether the conflict is a war of choice or a homegrown insurgency, and other factors, making the dynamics of an unfolding Taiwan-China conflict particularly difficult to predict in advance. Each decision, perhaps especially Taiwan’s, could influence the decisions of regional actors.

What does this mean for how Washington should approach its allies and partners about Taiwan? First, the United States should lead a series of detailed discussions with key allies about their roles in different contingency scenarios involving China and Taiwan.31 For some, these discussions should probably go hand in hand with consultation about other contingencies, such as possible flash points in the East China Sea or South China Sea. These conversations should begin quietly, and many of the details can and should remain private and classified. However, if these discussions do not ultimately engage the publics in the United States and allied countries, then there will not be political support for participation in a contingency, and alliance coordination is likely to founder.

This will be especially important if part of Beijing’s strategy in the early moments of a contingency is to split the United States from its allies and partners or in the event of a protracted conflict, in which divergences among alliance partners could emerge over time. Furthermore, the United States and its allies must come to terms with the reality that the initial phases of conflict could produce high casualties that intensify domestic political debates and alliance disagreements.

These discussions must include a diplomatic and a military-operational component, as successful signaling could play a crucial role in preventing the above scenarios from occurring in the first place. One risk is that Beijing might not believe that key allies would fight in a contingency, increasing the possibility of China stumbling into an otherwise deterrable conflict; the other is that efforts at deterring conflict are misinterpreted as provocative, creating an unintended escalatory spiral. It is therefore crucial that the United States carefully balance the need to communicate a reliable deterrent with avoiding unnecessary provocations that could trigger a conflict.

The United States and its allies and partners should retain the high ground by clearly reiterating their commitment and openness to a peaceful resolution of cross-Strait tensions, however improbable one appears at present, while ensuring that deterrence signaling is clear and capabilities adequate. This is a delicate balance that will be easier to strike if Washington can come to an agreement with Canberra, Seoul, Tokyo, and other allies and partners before a crisis and if some baseline expectations about ally and partner responses can be clearly signaled in peacetime. Those discussions should include planning for how the United States and others would support countries against possible retaliation by China—not just military but also economic, and especially in protracted conflict scenarios.

What does all this mean for US military posture and the Biden administration’s regional strategy? As it stands now, the United States will have to be prepared to not only “fight tonight” but also fight far from home with limited ally and partner support. In the future, administration officials should make efforts to avoid the kinds of tensions over basing arrangements that have taken up time and attention in the US alliances with both South Korea and the Philippines and try to focus on necessary, forward-looking conversations about regional contingencies that Washington should be having with its allies.32 Continued US efforts to distribute forces throughout the region are wise, as they limit coalition vulnerability to changing domestic political conditions in any one ally or partner, but the United States must also be realistic that its dependence on Japan and Australia may increase for both basing and some key niche capabilities.

These discussions need to involve not only allied conventional capabilities but also US nuclear posture. The United States will also need to have difficult discussions with its allies and partners about the implications of potential nuclear threats or escalation from China, particularly given Beijing’s recent modernization of its nuclear forces.33 The recent discussion of escalation risks with allies in Europe following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine highlights the urgency and relevance of such consultations.34

Finally, what does this mean for US force structure? American discussions with Taiwan about defense procurement and planning need to occur with the changing regional context in mind, while still being mindful of realistic expectations in a crisis. The contingencies described above require greater emphasis on a set of forces that can credibly deny Beijing the ability to take the island or prevail in a protracted coercive campaign, and they probably require a renewed discussion about the urgent need for Taiwan to rethink its approach to military manpower, especially reserve training and mobilization.35

They also require Washington to think about, and discuss with Taipei, the capabilities required to survive a protracted blockade after an initial invasion attempt fails. Shorter contingencies would put a premium on small and survivable systems on Taiwan combined with American undersea systems, long-range stealth aircraft, and ground-based missile forces. Longer contingencies would require mine clearing, survivable logistics, and deep munitions stockpiles sufficient for a protracted conflict.

The major bureaucratic losers in this construct would likely be large land units, short-range fighter aircraft, and less-survivable elements of the surface fleet. At present, however, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan have all invested significant sums in relatively expensive and vulnerable systems, meaning all three will need to consider more denial-focused postures, as Australia has recently done in its 2020 Defence Strategic Update.36

The United States should be talking with and pressing its allies to develop their own anti-access capabilities rather than replicating the power projection capabilities of US forces. Doing so would help ensure that the United States and its allies and partners have the capabilities needed to credibly deny Beijing the ability to invade or coerce Taiwan, which will be especially crucial if the United States can expect only limited basing access and force contributions from its regional allies and partners.